Added on 1/7/2025

By David Llada

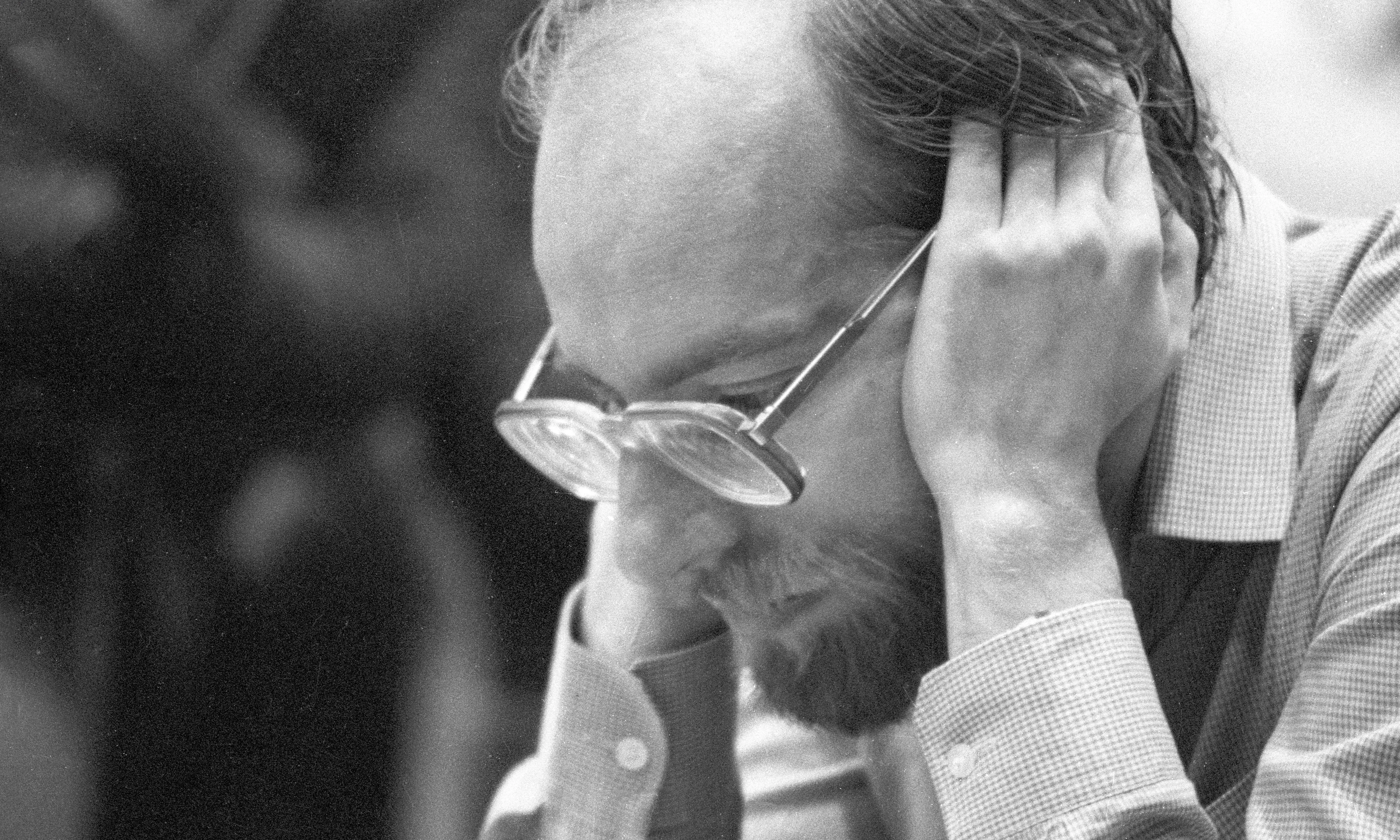

There are a handful of people about whom it has been said that they’re “too smart to become World Chess Champion.” Magnus Carlsen famously said this about John Nunn, for instance. The same sentiment applies to Robert Hübner, one of the greatest German players in history, who passed away this weekend at the age of 76.

Hübner was nothing short of an intellectual colossus. Yet, in true Socratic fashion, he was often quoted as saying he knew little—or close to nothing—about various subjects. The reality, however, was quite the opposite. He was a scholar in every sense, more often referred to as “Dr. Hübner” than “GM Hübner” because chess, indeed, was neither his profession nor his primary passion, despite his reaching the number three spot in the world rankings.

“Chess has never been so important,” he admitted to Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam in one of the few interviews he ever gave. “I enjoy it, and of course, it has filled my life, but I think that I can easily quit playing chess. I don’t think I am emotionally attached to this activity.”

It was his father, a classical philologist and teacher of German, Latin, and Greek, who taught him to play chess when he was five. Clearly, these interests were passed down to his son. After completing his studies in ancient languages, Hübner spent nearly a decade working at the University of Cologne —the city where he was born and where he died.

A consummate polyglot, Robert specialized in papyrology, deciphering and translating ancient documents, a work to which he often added historical or philosophical context.

“The study of philology is an attempt to approach man, to get a grasp on the subjective side of life. Man tries to depict reality through language. This is why language is of great importance,” he said. “Language is an old and impressive tool to approach reality, and also a wonderful toy. I am really astounded that this fact is so little appreciated today,” he added in the same 1996 New in Chess interview.

He was fluent in about a dozen languages and could understand a few more. Some of them were dead languages, and some others were quite “niche”, like Finnish. As the story goes, after playing a fascinating game with GM Heikki Westerinen who spoke only Finnish, Hübner’s frustration at their inability to communicate led him to learn the language “with great pleasure and considerable effort.” He was drawn to its limited, insular culture, which, like chess, provided an escape from the chaos of the world. His interests were distinctive: he had never heard of Elvis Presley but owned a vast collection of Asterix comics.

Hübner approached every task with remarkable perfectionism. He once became curious about Chinese chess (Xiangqi) and went on to become one of the world’s best non-Chinese players of the game. When an editor asked him to analyze his 25 best games, he spent thousands of hours crafting a 400-page volume, which he later described as “meagre.”

On one occasion, Hübner traveled to Australia for a tournament but felt too exhausted upon arrival to participate. Instead, he proposed annotating the best game of each round as a substitute—a tradeoff the organizers considered an upgrade. That shows to what extent his analyses were valued!

It’s clear to me that this aspect of chess brought him more satisfaction than competitive play. “Long analyses are an attempt to improve the game in hindsight, to transform the imperfect piece of work that is a game of chess into something closer to perfection,” he said.

Hübner’s competitive career took off in 1970 when, despite not yet being a Grandmaster, he tied for second place at the Interzonal Tournament in Palma de Mallorca, behind Bobby Fischer, whom he drew. Over the next two decades, he played in four Candidates Tournaments for the World Championship.

His first three attempts, when he was in his prime, ended in unusual circumstances:

• In 1971, in Seville, he was tied 3-3 with former World Champion Tigran Petrosian after six games. However, after blundering a piece in the seventh game, he forfeited the match, citing the noise from spectators, which he said made it impossible for him to concentrate. Hübner’s sensitivity and adherence to principles were well-known. At a later tournament in England, he forfeited a final-round game because the start time had been moved up two hours from what was stated in the invitation sent six months earlier.

• In 1981, he defeated Adorjan and Portisch in the quarter- and semifinals to reach the Candidates Final against Viktor Korchnoi. After six games, Hübner led by one point, just steps away from becoming Anatoly Karpov’s challenger. Yet, he abruptly withdrew from the match. He never fully explained his decision, stating only, “There are a number of reasons. Some are private in nature and not suitable for public discussion,” he said in an interview for Der Spiegel, published under the headline ‘Not like a monkey in a zoo.’ He added, “It’s not as if the evil world prevented me from finishing this match. I made mistakes myself, which I don’t want to comment on, and as a result, I found myself exposed to additional outside pressure. I didn’t feel able to play chess with the commitment and level I demand of myself.”

• In 1983, Hübner faced Vasily Smyslov in the Candidates Quarterfinals. This time, all 10 games were played without incident, and the match ended in a 5-5 tie. Four additional tiebreak games also ended in a draw. The score was still even, and since ‘doing a Magnus’ and sharing the title was not a possibility, the regulations stipulated that a roulette wheel would be used to break the tie.

So, on the evening of 20 April, 1983, Smyslov and the match arbiter Willy Kaufmann headed to the Casino Velden, located some 500 meters from the venue where the games had been played. Hübner went home and refused to attend. If the ball plunged into the black numbers, he would win. If it landed in red, Smyslov was the winner. At 8 pm, the ball started rolling… and to make things even more nerve-wracking, it landed into zero on the first try! They tried again. ‘Trois, impair, rouge’, announced the croupier, and Hübner went out.

Hübner still had one more shot at the title in 1991, when he reached the Candidates Eighthfinals. He lost to Jan Timman in Sarajevo, 4½-2½, in a rather uneventful match, considering the previous ones. Robert was already 42 and past his prime years. Kasparov was the man to beat, Short the most qualified challenger, and the likes of Anand, Ivanchuk, and Polgar were about to take over the chess world.

This was the closest post-war Germany came to producing a World Chess Champion. Hübner himself viewed chess as secondary. “It’s true that, to me, chess is not an important activity. I always found my other pursuits more valuable. I felt a need to prove that I was capable of more than simply pushing wood. It had nothing to do with social recognition, which you won’t find in this field anyway. I had to prove it to myself.”