Added on 12/4/2024

Game 8: A Hypermodern Rollercoaster

By David Llada

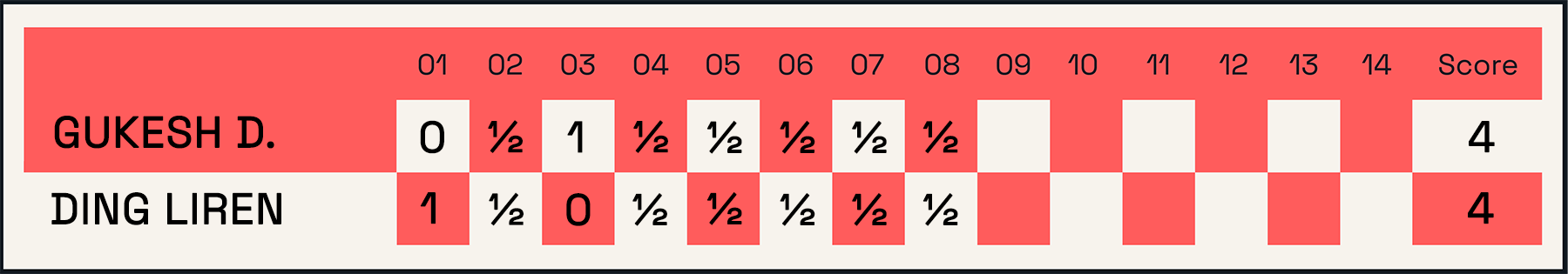

Ding and Gukesh made a draw in the eighth game of their match in Singapore, the fifth consecutive one, which leaves the scoreboard at 4-4.

At the media center, I share a table with my friend Leontxo García -- ‘Uncle Leo,’ as I call him after so many years of traveling the world together. Arguably the most prominent figure in today’s chess journalism, he has covered every World Championship since 1985.

And yet, this seasoned veteran was at a loss for words to describe the intense and exciting chess we have witnessed in the last two games of the World Chess Championship in Singapore. ‘How can I summarize this game with so many twists and turns?’ he wondered. ‘What headline could possibly do it justice?’

He made it sound like he was grumbling, but in reality, he was rejoicing. His face lit up like a kid in a candy store. His visible joy only added to my own.

As we mentioned in our previous report, impeccably played games are rarely the most exciting. The eighth game of this match was far from perfect. But beyond perfection, it had everything: originality, surprises, shifts in advantage, time pressure, and, of course, historical significance. After all, a title is at stake, and two and a half million dollars are on the table.

All this made the eighth game one of the greatest battles we’ve witnessed at a World Championship, at least in this century.

In fact, this game began with an opening approach by Ding that harkens back to another era: the Hypermodern school of chess, born in Central Europe in the 1920s.

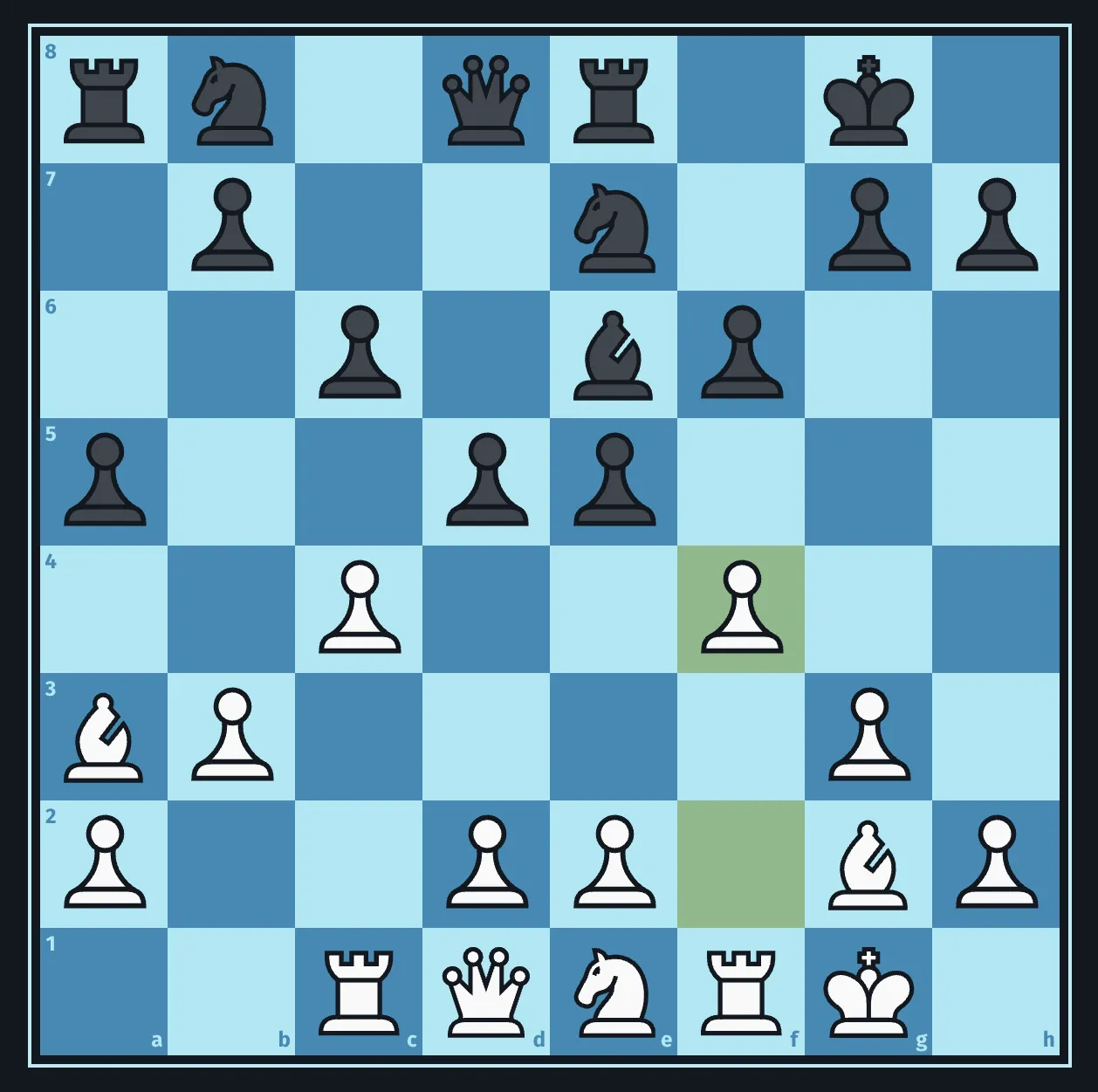

The World Champion, playing White, chose the English Opening, allowing Gukesh to occupy the center with his pawns, intending to turn them into targets of attack later on. Just look at this position after the move 14.f4:

Challenging Tarrasch’s old dogma that the center must be occupied by pawns, the Hypermodernists advocated for controlling the center with distant pieces and dismantling the opponent’s pawn structure with carefully timed pawn breaks from adjacent files.

Aaron Nimzowitsch was the founder and leading proponent of this new school, while Réti, Tartakower, Breyer, Bogoljubov, and Grünfeld contributed significantly by creating numerous opening lines based on its principles, greatly enriching chess theory.

As the game progressed, events unfolded largely in favor of the World Champion’s plan. Ding successfully opened the position and enhanced the power of his bishop pair. Gukesh, however, attempted to complicate matters, banking on the fact that Ding was, once again, under significant time pressure. What followed was a chain of mistakes from both players.

It’s simply impossible to capture this game's drama in a written report. My advice? Head to Agadmator’s video recap, linked at the bottom of this article, and watch it. Even better, set up a physical chessboard next to your screen to pause the video and analyze critical lines the old-fashioned way. Trust me: if you only have time to study one game from this match, let it be this one.

Throughout the game, and based on comments made by the players at the press conference, it seems that Ding tends to underestimate his positions, while the young Gukesh has a habit of overestimating them.

‘Ding is desperate for a draw... and Gukesh wants to lose. Let’s see how this comedy ends!’ wrote the experienced GM Ivan Sokolov on Twitter, after the Challenger rejected a draw by threefold repetition when his position was objectively worse.

The decision was so surprising that many assumed the Indian star was bluffing or exploiting his opponent’s insecurities. However, Gukesh denied this at the press conference and expressed his surprise upon realizing how precarious his position had been. ‘Looking at the engine lines, it was obviously a misjudgment!’ he admitted.

We still have six classical games ahead of us in the match. If you ask me, I am okay with none being ‘perfect.’

Agadmator's Game 8 video recap