Added on 7/15/2019

Vitolins was born on the 15th of June 1946 in Sigulda, Latvia, close to Riga. He was nine years old when his father took him to the first chess coach, Felix Tsirtsenis. Vitolins' talent emerged shortly after, and he became one of the strongest juniors in URSS. "He was the best among us," said GM Yury Razuvaev. The chess aficionados will always remember Alvis, and that is mostly due to the fertile pen of Gennadi Sosonko, the Russian GM who moved to the Netherlands in 1972. In his fantastic book "Russian Silhouettes," Sosonko draws the biography of some of the Russian protagonists of the Chess scene: Tal, Botvinnik, Geller, Polugaevsky, Vitolins, Levenfish, Zak, Furman, Koblentz.

I will use part of Sosonko's book in this article. If you have a chance to read the book, do it; it's worth your time! To know our game, in my opinion, one needs to know the great players, men and women, from the present and the past. And I am not talking only about the games of these great players; the moves are like a painter's brush strokes: if you don't know the artist, you can't understand their art.

His great fellow-countryman, Mikhail Tal, wrote about Vitolins during the preparation of the match with Korchnoi: "we were in Riga, in Summer; I saw a man enter the room. He was tall, slightly sad in his look, a bit lanky: it was Alvis. I remembered him because we had played in Leningrad several years before when he was a youngster: an opposite color bishop endgame, which was drawn, but Alvis was able to see and realize a dangerous initiative. I was in time trouble, and he offered me a draw. I understood Alvis didn't want to win on the clock. Right after the game had ended, he started showing me how I could have forced the draw anyway.".

Alvis was a peculiar man, whose nickname was "Dlinny," due to his physical stature. He was an introvert. Vitolins won the Latvia national championship 10 times, from 1973 to 1989. But he didn't get the chance to play chess outside the URSS, and rarely he could play out of the boundaries of the Baltic region. Only at the beginning of the '90s, Alvis participated in some tournaments in Germany, but by then he was over 40, and his peak was irremediably behind him. He never had the chance to obtain the GM title, which is a shame.

Vitolins was the typical representative of the Latvian school. His play had some of the characteristics of Tal's, and of that of contemporary GMs, such as Shirov and Shabalov: King under threat, everything hanging on a fragile thread, positions that crumble and change at every move.

The initiative. This was Alvis' totem: action at all costs, sacrificing pawns to give the pieces maximum energy. The opening? Only 1. e4 as White! Why? Because "with 1. e4 you win the game, or at least you get a decisive advantage.".

Vitolins has contributed to open and semi-open variations, from the Sicilian Rauzer to the Alekhine defense, to the Cochrane Gambit. In a New in Chess article, Vitolins wrote that "even in a variation apparently old and worn out, you can find new ideas because chess is limitless.".

Alvis was gifted with an excellent memory, and he was full of ideas. Maybe he had too many ideas, at the point he could lose the grasp of the essential principles; which was - according to Sosonko and others - his weakness, together with the evident annoyance when finding himself in inferior positions. It may have been better to use some patience, but Alvis' nature didn't allow him to tackle the game differently.

Players like Alburt or Razuvaev said that against Vitolins it was essential to play classical theory and with a rigorously wait-and-see tactic, knowing that Alvis sooner or later would have gone astray in the searching of some intriguing but unsound combination.

Sosonko recalls how Alvis liked to place his bishops almost always on g5 and b5, especially in b5. And how Vitolins sometimes played "Bb5" without even caring to know if there was a pawn on a6!

Vladimir Tukmakov said that he had played several times against Vitolins, but that he couldn't remember to have exchanged more than three words with Alvis after the game: "he had a terrific talent, but he was not communicative at all and I immediately feared that his gift was going to be wasted.". Too bad, because at the beginning Vitolins had raised big hope, after his successes in various youth competitions.

Unfortunately, Vitolins, more than fight his opponents, had to challenge himself, since he was a teenager (even his coach Tsirtsenis mentioned it), against the symptoms of schizophrenic illness, that dogged him all his life.

He often took pills, but the drugs influenced his thought processes and his responsiveness.

Alvis was able to analyze a position on a small magnetic board for a whole night and the day after, and then sleep two days in a row.

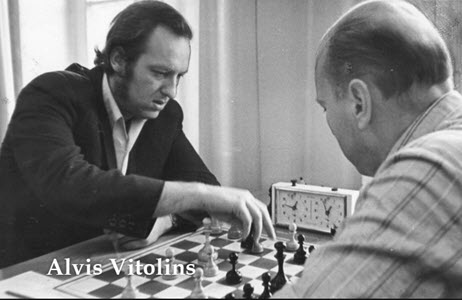

Vitolins was tall and a big guy, with long sideburns, that in his young years made him look a bit like Elvis Presley. But he could look like one of the captains of the big English freighters in the nineteenth century.

Sosonko continues: "He was as big as naive and gentle ... childish and defenseless. He never married and has almost always lived with his parents. Alvis didn't have many friends and none outside the world of chess.".

Alvis' best friend was another strange man, the talented Ashotovich Grigorian, a significant Armenian promise in the 70s, who took his life in 1989 in Yerevan when he was 42. They had similar mental issues e similar ways to play chess, especially in blitz, where both were nearly invincible.

Vitolins has lived only for chess and into chess, but chess itself in the years became his ghetto. He lived into his club where he played blitz until late at night, and often he slept there, without getting back home.

He got fired by the federation, for which he worked as a coach. In 1996 he lost both his parents, and after a few months, on New Year's Eve, his psychiatrist died too. It was too much for his fragile equilibrium.

Some years ago, in his blog Xadrez Memòria, Arlindo Rodrigues Vieira from Portugal described, with shreds of delicate fantasy, the last moments of Alvin Vitolins' life, paying him, so far away from home, the best possible tribute. And, strangely, such a tribute comes from Portugal, one of the least active countries in Europe chess-wise. Here is a synthesis I extracted from the moving images and words written by Arlindo.

It's just past dawn, on February the 16th, 1997. A cold and grey dawn. Alvis gets his coat, dirty and worn out, even with some holes in it. Then he takes his loved bishop off the chessboard and put it in his pocket. He gets out and strolls toward the railway bridge on the river Guaja, in his Sigulda, one of the most beautiful places in Latvia, surrounded by medieval castles and forests. In the distance, the whistle of a train, which announces its imminent arrival. It's freezing this morning in Sigulda. Here we are. He stops for a second and breathes the frigid air deeply. Then he decides to move, with the same determination he used to place the bishop in b5: the jump! A sudden crack in the silence of the early morning, the ice shatters and opens, the river hugging in its deep waters Alvis' warm body. He was found several hours later: in his left hand, livid and frozen, he still held that bishop he refused to leave: he had made an eternal deal with it.

It's true: the goddess Caissa doesn't love all the chess players the same way.

Riccardo Moneta wrote the original article. Translated for the ICC by Sandro Leonori.